We sat down with Dr. Alexis Clark, Assistant Teaching Professor of Art History, to talk to her about impressionism, her book, Globalizing Impressionism and what’s on the horizon for her.

Why Impressionism?

As someone originally from Chicagoland, I had the incredible experience of regularly visiting the Art Institute of Chicago where I could look at all the wonderful paintings by Claude Monet and Gustave Caillebotte and Georges Seurat.

Then, as an undergraduate at Indiana University, impressionism seemed to be the cutting edge specialism where scholars were asking “big questions” drawn from Marxism and feminism–and I wished to be part of those conversations.

In your bio, you mention that “you’ve raised questions related to art and language style, translation and silent translators.” What are silent translators?

With “silent translators,” I’m adapting the idea of translation theorist Lawrence Venuti. I’m working to recover the voices of people who translated art-historical texts and, through those translations, facilitated the early-twentieth century circulation of books and articles across geographic and linguistic boundaries. There were different modes and motivations and legal structures for translation–none of them neutral. Ultimately, though, I’m interested in how translations allow us to understand how the modern world saw, and read about, the world of art.

Let’s talk about Globalizing Impressionism: Reception, Translation, and Transnationalism (Yale UP 2020), which you co-edited with Frances Fowle and was named one of the “most essential books in Impressionism.” What do you mean by globalizing Impressionism?

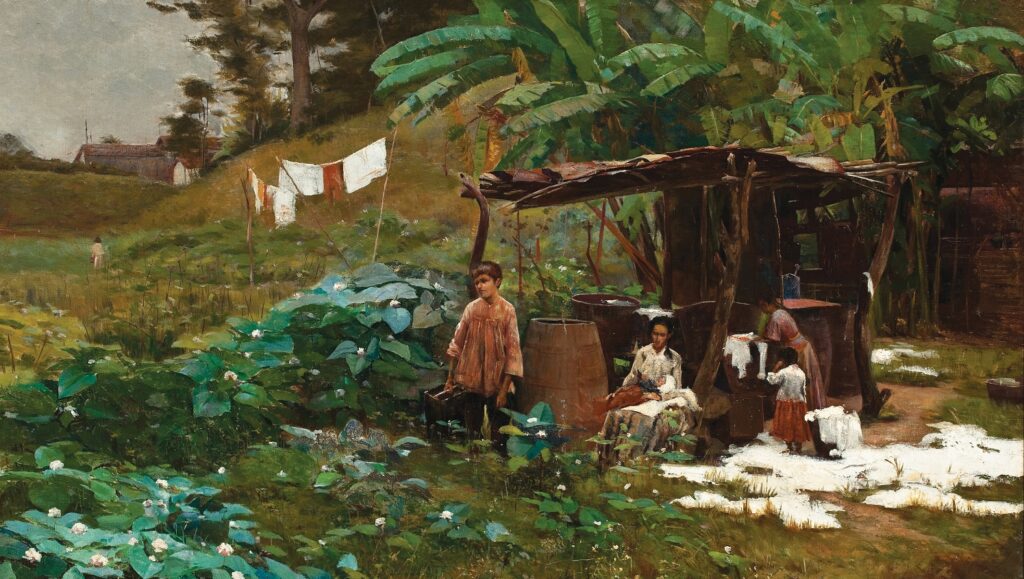

When we think impressionism, we tend to think Paris. But as Globalizing Impressionism and its contributors have underscored, impressionism circulated far and wide as a set of artistic techniques and practices, as an idea connecting those techniques and practices to conceptions of modernity, and as a polysemous term well into the twentieth century. Globalizing Impressionism has temporally and geographically expanded how we study impressionism.

How might we differently understand, and write, the history of impressionism when we account for artists living and working in 1920s and 1930s Brazil who may or may not have traveled to Paris and visited its museums but who, regardless, saw themselves as also engaged with impressionism? Or how might we differently understand, and write, the history of impressionism when we account for impressionism as taught as part of official arts academies in colonized parts of the world?

Globalizing Impressionism asks questions like this–and I am so proud that this volume has made an impact on the subfield. It was important to me and to my co-editor, Frances Fowle, that our anthology include a global community of scholars living and working in different parts of the world in different languages and across academic ranks. In rethinking impressionism, it was imperative to us to include platform voices and perspectives not always included in discussions.

In tandem with its chapter-by-chapter content, the organization of Globalizing Impressionism makes a second argument. Writing global histories of art ought to be done collaboratively and collectively. No one art historian can write the definition of “global impressionism.” To attempt to do so, would be to risk simplifying a truly complicated story. That’s a topic for a second interview, though!

What’s on the horizon for you?

A lot! Later this spring, I’m speaking at the University of Montreal on the transhistorical legacy of impressionism as seen in 1980s and 1990s paintings by Mark Tansey.

I have several forthcoming publications. In fall 2025, I’m publishing a co-authored state-of-the-field report on impressionism studies with colleagues based in Europe (Allison Deutsch), China (Jung Choi), and the UAE (Dalila Meneen). Then, for 2026, Tate Britain has invited me to write a catalogue essay for their upcoming exhibition on North Carolina-connected artist James McNeill Whistler and his family’s Confederate sympathies. With this research, I’m working to restore a discussion of politics and race in Whistler’s work including his Arrangement in Black and Grey: The Artist’s Mother. And I have other publications forthcoming in 2026. Check back!

Lastly, I wished to highlight a new organization which I co-founded coincident with the 2024 celebrations of impressionism at 150: Impressionist Futures Group (IFG). Like my research program, my group aims to build networks across geographic, linguistic, and academic lines through an exciting roster of public events. At the College Art Association conference, I’ll be presenting on IFG and the importance of collaboration as art-historical practice.

What courses are you currently teaching?

I’m teaching the whirlwind survey Renaissance to 20th Century Art. We’re attempting–and I’d emphasize attempting!–to cover six centuries of art. Because cutting across periods and places is a challenge, I have concentrated this course on three art world cities: Venice, Amsterdam and Paris. Though our class’ focus remains on art produced in and around these cities, I also trace their connections to Asia, Africa, and the Americas. TA Lilly Underwood and I are taking the students on tours of Renaissance, Baroque, and modern art collections at the NCMA.

I’m also teaching an honors section of History of the Art of Photography. Last week, we made our first visit to the Ackland Art Museum to view a sample of photographs not always on display. I’m so excited to share area resources with our students–their eyes light up to see work by photographers studied in our course.

Whenever possible, I connect my research and professional service to the classroom. I’m already dreaming and scheming about ways to update my “Impressionism” course for fall 2025. One option might see me connect NCSU students with students at other universities, asking them to develop a co-authored research project.

Is there a non-French artist who identified as an impressionist or associated with the French impressionists whose work you like?

So many! How to choose only one! I’ll name Eliseu Visconti and Georgina de Albuquerque and Francisco Oller here. But there’s so much to see and learn!

- Categories: