Public History MA Student Emma Jo Donnelly Curated an Exhibit on North Carolina’s Environmental Justice Movement

Emma Jo Donnelly presented a historical exhibit at the twenty-fifth annual North Carolina Environmental Justice Summit, held on October 18-20, 2024 at the historic Franklinton Center at Bricks in Whitakers, NC. Emma completed the historical research and curation for the exhibit, and Luma Kennedy, the Communications Manager of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN), designed the graphics.

I first discovered my interest in historical research based on community needs when I attended Florida Atlantic University’s Ethnographic Field School in Ecuador in 2019. I learned that my professors’ anthropological and archeological studies had supported a local community in their self-advocacy for communal land rights based on their ancestral connection. Since then, I have remained devoted to public history projects that assist underserved communities in addressing their concerns and achieving their goals.

That commitment motivated me to pursue a master’s degree in Public History at North Carolina State University. In a course during my first semester, Professor Tammy Gordon offered invaluable instruction on developing needs-based public history projects. The insights I gained in that class about centering community needs and perspectives in historical work have remained central to my research and public-facing projects.

When Dr. Rania Masri and Dr. Chris Hawn, two of the three co-directors of NCEJN, visited my graduate seminar in American Environmental History at NC State in Spring 2024, they informed the class of their organization’s long term commitment to research driven by communities impacted by environmental injustices. While their research involves public health and environmental science methodologies, I felt profoundly inspired by the strategies they use to center community perspectives in every step of the research process. Dr. Masri and Dr. Hawn also mentioned their organization’s urgent need for help documenting their history. I immediately knew I wanted to assist with that project, as it offered the unique opportunity to develop a needs-driven public history project for an organization devoted to supporting communities with grassroots organizing against life-threatening public health and environmental injustices.

In the summer of 2024, NCEJN hired me as its first Archival and Curatorial Intern to build an archive, oral history project, and exhibit on the history of this non-profit organization and the Environmental Justice Movement in North Carolina. In 1982, residents of Warren County—a low-income and majority Black county—protested en masse the State of North Carolina’s decision to dump 60,000 tons of soil contaminated with dangerous carcinogens called polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). While the State still dumped the waste in Warren County, these protests ignited the Environmental Justice Movement. Motivated largely by shared concerns about Black land loss and the racially discriminatory siting of industrial hog operations, Black communities in eastern North Carolina founded NCEJN in 1998 to coordinate and expand their grassroots organizing efforts. Since then, NCEJN and its partners have led a robust movement for environmental and racial justice that has achieved impressive improvements in workplace and community health, safety, and wellbeing statewide.

As I collected documents for NCEJN’s archive, I realized that most of the history of the organization remained in its members’ memories. Halfway through the summer, I began conducting oral history interviews, which constituted the basis of the historical exhibit I presented at the Summit. My undergraduate experience working under the direction of Dr. Paul Ortiz at the community-based Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP) at the University of Florida gave me vital insights which I incorporated in structuring the historical projects for NCEJN. At SPOHP, I had learned crucial strategies for building community relationships, navigating the complexities of the interview process, and centering narrators’ perspectives throughout the project—from identifying questions to developing public projects. As NCEJN staff discussed the ways in which my historical research could support their ongoing organizing efforts, I modified my archival process to address these needs and make the information more accessible for their purposes. My collections efforts and oral history interviews are ongoing, so the exhibit I presented at the Summit incorporated the research I had completed as of September 2024.

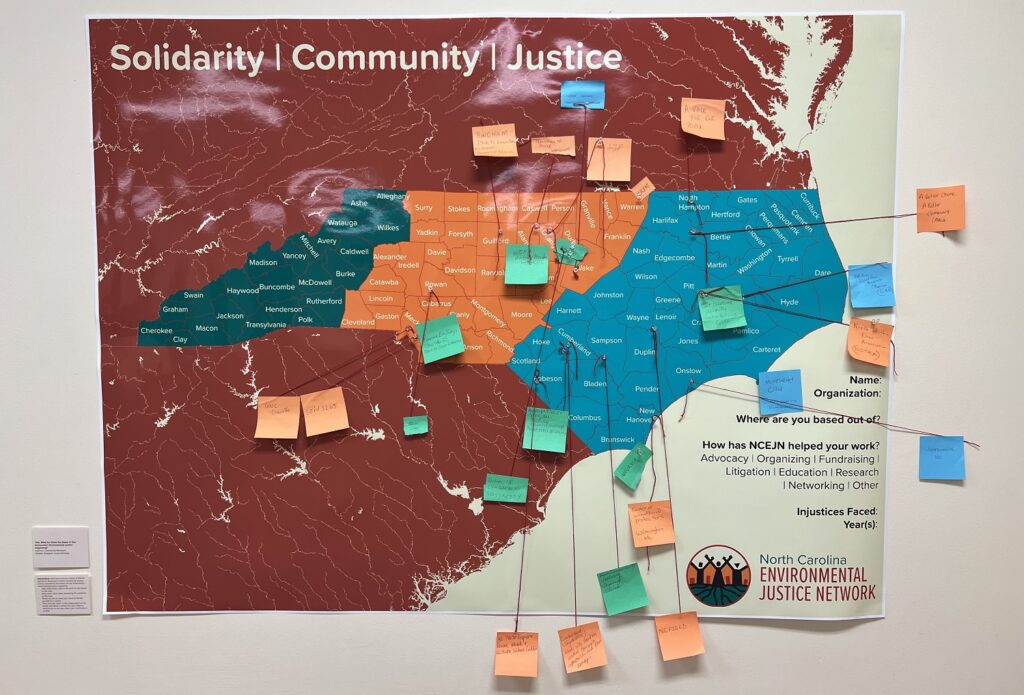

The exhibit consisted of foundational documents and a timeline of key events in the history of NCEJN, oral history excerpts, and interactive stations for a community history project on the Environmental Justice Movement. I saw inviting community members to participate in the exhibit as crucial for multiple reasons. Most significantly, the involvement of community members was key, because NCEJN is deeply community-driven and has consistently remained committed to prioritizing community needs and perspectives in its work. Furthermore, time constraints did not permit me to complete all of the oral history interviews prior to the creation of this exhibit, so community participation crucially broadened the experiences and memories included.

At the Summit, many community members participated actively in the exhibit and expressed their gratitude for this documentation of their history. I also provided a sheet for attendees to sign up to participate in oral history interviews, and the fact that several people did so will be incredibly important for my expansion of this historical research for NCEJN.

Attending the Summit also deepened my understanding of the ways NCEJN engages with communities and the strategies it utilizes in its organizing efforts. In all sessions I attended, community members shared stories about their successes and challenges and offered wisdom for ongoing struggles. I felt moved by these communities’ solidarity and the depth of their interpersonal relationships. Many of the folks I interviewed explained that they see the Summit as a sort of family reunion. Though it was my first time attending, I felt their love and care for one another and their commitment to creating a welcoming space for newcomers.

I am immensely grateful for this opportunity to record the history of NCEJN and North Carolina’s Environmental Justice Movement. I look forward to continuing this research and exploring the ways in which knowing and sharing the history of the movement can support these communities in dismantling structural racism and demanding justice.

For more information about the history of NCEJN, and to get a closer look at the historical timeline from the exhibit, please follow this link: https://ncejn.org/about/#our_history.