Drawing Democracy: North Carolina’s Gerrymandering History

This post was adapted from an exhibit by Historians for a Better Future and edited by Derek Huss, who holds a Public History MA from NC State, and Katie Schinabeck, a Public History PhD Candidate at NC State.

Introduction

Gerrymandering has entrenched itself in North Carolina politics. Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing legislative districts in order to benefit a certain political party. As the image below demonstrates, a geographic area evenly split between the two political parties can be divided so as to weaken the vote of one group. Since legislators draw districts, when a political party holds a majority they can draw districts that will keep them in power even if the political preferences of constituents change.

Gerrymandering is a problem because it distorts democracy. Americans vote on representatives with the understanding that each vote will count equally, but gerrymandering shifts political districts so as to dilute the voice of individuals within the political system.

The 2018 election demonstrated the extent and impact of gerrymandering in North Carolina: despite winning 50.3 percent of votes, Republicans occupy 10 out of 13 (76%) congressional seats.[1] As the accompanying graph shows, the end result in a non-gerrymandered state would look much similar to the popular vote. While gerrymandering is a continuing problem in the state, it isn’t a new problem.

Gerrymandering and White Supremacy

During Reconstruction, Progressive Republicans in Congress gave federal protection to African American voting rights with the 15th Amendment. In response, North Carolina Democrats grouped as many of North Carolina’s Republican voters as possible into the state’s second congressional district, which became known as “the Black Second”. The Black Second consisted of counties in the northeastern and coastal regions of North Carolina. This district would see consistent African American majority wins between 1868 and 1898. However, the gerrymander succeeded in curbing African American influence in politics by making it nearly impossible for African American voters to elect a Republican anywhere else in the state. George Henry White, an African American politician, won the Black Second in 1896 and again in 1898. North Carolina’s white Democrats effectively disenfranchised its African American citizens after 1898, leading to White’s departure from Congress. North Carolinians did not elect another African American Representative to Congress until 1992.

‘One Man, One Vote’

The Civil Rights Movement was in part a response to disenfranchisement. In North Carolina, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was founded at Raleigh’s Shaw University in 1960. They used the slogan of ‘one man, one vote’ as a call for equal representation. In 1964, marches and sit-ins in Chapel Hill highlighted injustices in the seemingly enlightened college town. One protester held a sign emblazoned with “Make democracy more than a word in Chapel Hill,” calling into question the town’s commitment to social equality and political agency.

In addition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Civil Rights activists won a lesser known victory for voting rights in the US Supreme Court case Baker v Carr (1962). In this case the Supreme Court gave protection to the idea of ‘one person, one vote’ by ensuring states would have to redraw districts based on population changes. Baker v Carr also caused a lasting impact on future state redistricting cases by giving federal courts the right to weigh in on state district cases.

Image courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture

A Complicated Issue Emerges

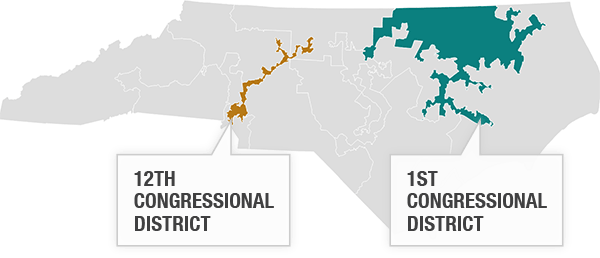

The Voting Rights Act allowed state legislatures to create majority-minority districts—a district in which a historically disenfranchised minority comprises the majority population. In 1990, the Democratic-led North Carolina General Assembly redistricted the state and created one black majority district, District 1, and another majority-minority district, the now notorious District 12. Republicans challenged the map in the Supreme Court case Shaw v. Reno. The plan, Republicans argued, was a partisan power grab, because majority-minority districts tended to vote Democrat. Democrats countered that the districts were necessary in order to adhere to the Voting Rights Act. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled the redistricting plan an illegal racial gerrymander not because it established majority-minority districts but because it did so with such a bizarrely shaped district.. The case effectively weakened the Voting Rights Act by creating narrow standards for what constitutes racial gerrymandering and what constitutes fair representation. What followed was a continuous string of court cases involving North Carolina voting districts, stretching from the 1990s to the present.

Gerrymandering, Redistricting, and Voting Today

The 2010 election cycle ushered in the latest phase of North Carolina’s gerrymandering saga. Prior to this time, opponents of the state’s approach to voting districts focused their criticisms on the serpentine 12th Congressional district. After assuming control of the NC General Assembly in 2011, Republican lawmakers employed their Rucho-Lewis plan to redraw both federal and state voting districts. Challengers of the 2016 and 2018 North Carolina federal congressional districts made by the Rucho-Lewis plan argue that the map uses partisan gerrymandering to dilute the voting power of NC citizens.

Since 2016, the case has gone back and forth between district courts and the US Supreme Court. In March 2019, the Supreme Court heard arguments for Common Cause/League of Women Voters v. Rucho. With this case, the Court had the potential to render partisan gerrymandering unconstitutional. In its decision, the Supreme Court admitted that partisan gerrymandering is a problem, but one that is out of its jurisdiction, thus leaving the question of partisan gerrymandering at the state level. The NC Supreme Court will hear a very similar case in July 2019. The main argument in that case, Common Cause v. Lewis, is that the current maps are in violation of the state Constitution. There are also several bills that have recently been introduced to the state legislature that call for independent or non-partisan commissions in charge of fair creation of voting districts.

Gerrymandering affects everyone by weakening citizens’ political voices. While remedying gerrymandering requires institutions like courts and legislatures, it’s organizations of everyday people like the League of Women Voters and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee that compel those institutions to do so. The current court case in front of the North Carolina Supreme Court or the bills in the state legislature could protect North Carolinians from this distortion of democracy in the future.

** If you’re interested in the history of gerrymandering in North Carolina, contact Historians for a Better Future (historiansforabetterfuture@gmail.com) to learn more about our traveling exhibit, an expanded version of the information above, to your event.

[1] This number is subject to change as a result of the called for re-election in the 9th district. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/11/09/one-state-fixed-its-gerrymandered-districts-other-didnt-heres-how-election-played-out-both/?utm_term=.2126c9446d1a;

https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/article221282920.html

- Categories: